Everyday Life

Cyril Hatt and Francis Ponge, the traces of a connection?

The oyster, the size of a medium pebble, is rougher in appearance, of a less solid colour, brilliantly whitish. It’s a stubbornly closed world. However, you can open it: you must then hold it in the hollow of a tea towel, use a chipped and not very frank knife, and get back to it several times. Curious fingers cut themselves, break their nails: it’s a rough job. (…)

Extract of “The Oyster” , in Le Partis pris des choses of Francis Ponge.

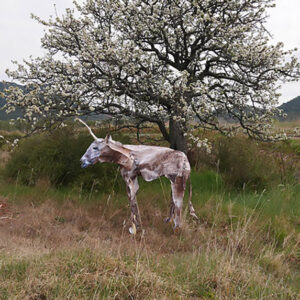

For two decades, Cyril Hatt has been creating a series of works focusing on everyday life, whether objects or animals: from musical instruments (guitar, trumpet, etc.), to the very trivial beer can and ashtray, including giraffes, pigeons, and baby elephants. When it comes to consumer products, the work of deconstruction/reconstruction generated by the artist’s photographic prism and the sculptural distortion via stapling are rooted above all in a denunciation of the consumerism specific to the counterculture to which he belongs.

Born in 1899 in Montpellier, not far from where Hatt now lives and works, Francis Ponge could be seen as a precursor to this series. This counter-current and iconoclastic poet owes his success in particular to the collection Le Parti pris des choses (1942). His quest for authentic description undoubtedly recalls the visual artist’s obsession with reproducing his distorted perception through his lens. Ponge deified the object after sometimes giving it human features. Hatt pays homage to trivial elements to better emphasize the extent to which their disposable and interchangeable nature endangers our humanity: behind every consumable, there is a consumer, and materialistic dependence ultimately changes the balance of power between the two elements of the equation. Is it the object that is used by this consumer? Or is the consumer consumed by his addiction to Having?

Thus, in the writings of Francis Ponge, as in the art of Cyril Hatt, commitment is expressed as a snub to the society of their time, somewhere between poetry, jokes (Cyril Hatt’s camera itself becomes the object of his work), and humor.

Tony Kunter